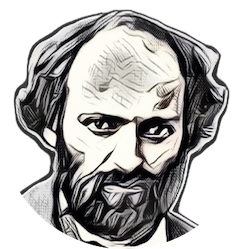

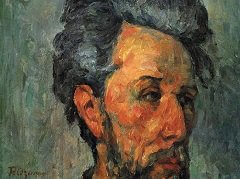

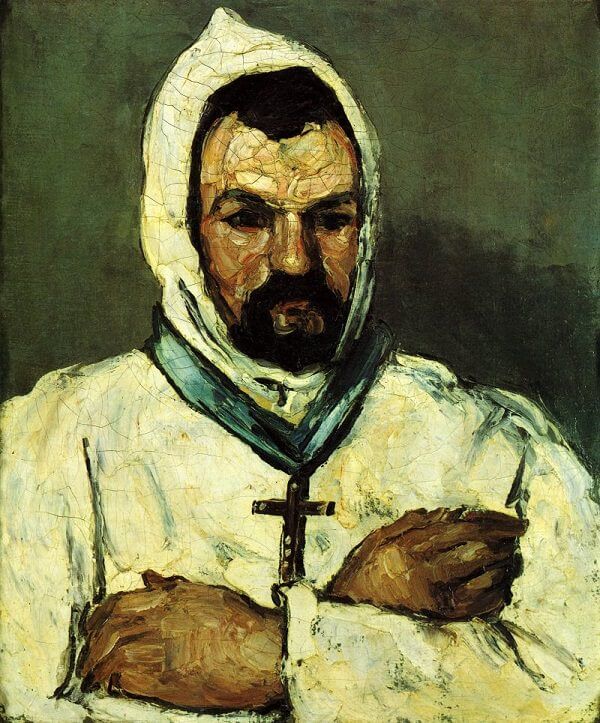

Uncle Dominic as a Monk, 1866 by Paul Cezanne

The young Cezanne made several pictures of passion and dark fantasy. In portraying his uncle - his mother's brother - in the costume of a monk, he avowed a desire for solitude and for mastery over the flesh. During this period he also painted a large canvas of the Temptation of Saint Anthony. The choice of the white Dominican robe is perhaps more than a play on the uncle's name. The order had been revived some years before by the preacher Lacordaire, an ardent religious figure who stirred the youth of France by his attempt to win the Catholic church for republican ideals and later opposed the dictatorship of the Emperor Louis Napoleon. Many painters, especially among the Romantics, were drawn to Lacordaire who founded a society for the renewal of religious art. The Dominican order was a retreat for despairing romantic spirits.

The painting of Uncle Dominic is not a true portrait, but something between an ideal symbol and a masquerade, through which the artist could re-live his own struggles and dream of release. Painted in the solitude of the family estate near Aix, it is the image of a strong, fleshy person who strives to contain his passions through the religious habit - it encloses the somber, powerful head yet allows the body to show its fullness - and through the self-inhibiting gesture, a crossing or reversal of the hands, which is a kind of resignation, a death of the self.

The opposites of the sensual and the meditative, the expansive and self-constraining, are well expressed here. The color is imbued with the pathos of the conflict. A scheme of white, grey, and black plays against the ruddiness and earthen tones of the flesh. We pass from white to black through a cold series of bluish tones and a warm series of yellows, reds, and browns. The cold, piercing gleam of blue in the neckpiece brightens the whole. The execution, rude and convinced, is of a rare vehemence, even ferocity, like an Expressionist painting; the palette knife is its chief instrument, raising a relief of thick pigment. Within the common intensity of the paint each large area has its own texture and rhythm of handling.

The conception has a certain grandeur through its simplicity. The figure fills the space to bursting, but is also rigid. The starkness of the form is moving. The dark spots of the face and hands are like three leaves on the common stem of the axis marked by the cross. This cross, in line with the vertical of the left sleeve and tying the head to the hands, is part of a longer double-armed cross formed by the lines of the left hand and sleeve - a remarkable invention that points to later works in which such continuities of neighboring objects are a constructive, anti-dramatic device. The projecting tip of the hood is a sensitive point, prolonging and narrowing the head and displacing its axis - a vaguely spiritual, even Gothic suggestion; it is like the pointed tips of the hands, through which these are further assimilated to the head.