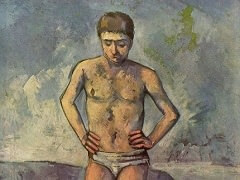

The Bather, 1885-87 by Paul Cezanne

The Bather, 1885-87 is a statue in a landscape; not of a bather but a man in thought. Completely absorbed in himself, he is welded to his surroundings: the color of his flesh is like the ground, and the shadow tones of blue, violet, and green, the rosy and lightened high lights, are like the water and sky. His great vertical form rests on a world of horizontal bands; verticals and horizontals belong together. The bent arms resemble the sloping rock profile at the right. The opening of the legs is like the fingers of water laid out on a contrasting ground. Besides the symmetry of the rock edge and the bent arm, there is the symmetrical pattern of the segments of sky between the body and the arms and the related belt - a tight construction of upright and horizontal forms. On the belt, the banded lines are seen together with the fingers above them, but also with the banding of the earth at the left - the reddish prongs of the ground which alternate with blue inlets of water.

It is a strange landscape, imagined in the studio, yet natural for the naked figure, his only possible milieu - empty, mostly barren, and delicate like revery. Figure and landscape echo each other and bear the same brushwork, the same substance of color, equally free, spotted, and changing. The main lines of the landscape coincide with divisions of the figure. The upper body is in the sky, the lower is on the earth. Where the knee advances, marked with red, begins a green band of the earth. The bent arms call out luminosities and turbulence in the adjoining sky, like the angels fluttering about a holy figure in old art.

The drawing is an effect of naive searching, an empirical tracing and fitting of the forms, a little awkward yet rhythmical and strong, and finally right; some touches, as in the well-articulated legs, exploit a past study; other parts are more arbitary and fresh. This drawing, so earnest and free, was a revelation to young artists about 1906 and helped to liberate them. The body is not stylized nor reduced, but reconstructed scrupulously according to an ideal of harmony and strength. It is a drawing without banality or formula, even a new formula.

But is it essentially a "pure form," an "abstract" construction? There is in this monumental bather a complex quality of feeling, not easy to describe. Rigorously tied to the landscape, the figure is nevertheless detached, unaware of the world around him. But the meditativeness is only half the story. The upper body is immobilized by its posture; it looks inward and closes itself. The man walks, yet holds his sides. This upper body is ascetic, angular, strictly symmetrical, and relatively flat, the lower body is more powerful, athletic, fleshy, modeled, and in motion - an open asymmetrical form. Two opposed themes are joined in one body, and this opposition appears also in the character of the sky and earth, one vaporous, the other more stable and solid. The drama of the self, the antagonism of the passions and the contemplative mind, of activity and the isolated passive self, are projected here. The contemplative dominates in the end, but the body remains warm in color, powerfully set, while the world - an enveloping void - is distant and cool.