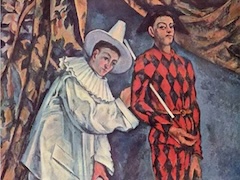

The Picnic, 1869 by Paul Cezanne

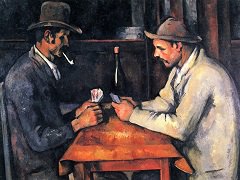

The ordinary meanings of a picnic are overlaid here by a strange, dream-like atmosphere. Above a tablecloth spread out on the grass, on which lie nothing but two oranges - the apparent objects of the meditations of the figures - hovers a tall, bent woman with loosened golden hair, a sibyl who holds a third orange in her extended hands, as if performing a sacramental rite or pronouncing an incantation. She turns her gaze to the frock-coated, gesturing man in the foreground; he resembles the young, prematurely bald Cezanne. In the distance stands a solemn, rigid figure, smoking a pipe, with folded arms like a guard or a celebrant of a ritual; on the left, a man and woman, dressed like Cezanne and the sibyl, go off into the dark woods arm in arm.

Painted not long after Luncheon on the Grass of Manet, at a time when the picnic was a favored theme as a type of modern idyll - a refreshment of the senses and the whole being through air, light, and informal play - this picture is a measure of Cezanne's distance from the mood of his contemporaries, even of those to whom he feels closest. His burdened spirit does not enter easily into the freedom and gayety of his friends. He is the odd man at the party, the one without a woman, and among the men in shirtsleeves he is exceptional in his more formal dress. He cannot surrender to the innocence of the occasion; it is full of mystery and doubts. The third fruit intimates a question.

In this troubled fantasy Cezanne was not far from Manet's scandalous picture. There two men in formal city dress sit with a nude woman - a second bathing woman is hidden in the distance under an exotic bird. In juxtaposing the naked and the clothed, Manet pointed too directly and dispassionately to the instincts behind the picnic.In Cezanne's mind the picnic called up hidden, personal meanings which the Impressionists ignored in their light-hearted images of the theme. The dog and the paired parasol and hat in the right corner belong perhaps to that underground sense.

Cezanne's early paintings are often regarded as immature sketches, too impetuous to permit the critical pondering of forms that gave order to his later work. Yet the abrupt, nervous execution and the roughness of detail should not hide from us the strength of the canvas; there is nothing banal in its forms. The concentration of the figures about the white cloth, the silhouetting of the tall woman against the dark woods, and the parallel tree trunk at the right, are striking effects. The young Cezanne was acutely aware of the grouping and found the right directions and spotting of colors for the tense expression he desired. Interesting for his later art is the continuity of the horizontal cloud and the edge of the woods; we see this device again in the edge of the tablecloth and the sibyl's hem. Time has darkened the color, submerging the nuances in the large areas; but the play of somber neutralized tones of warm and cool shows Cezanne's natural, even exquisite, feeling for harmony.