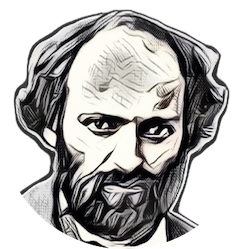

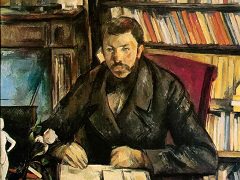

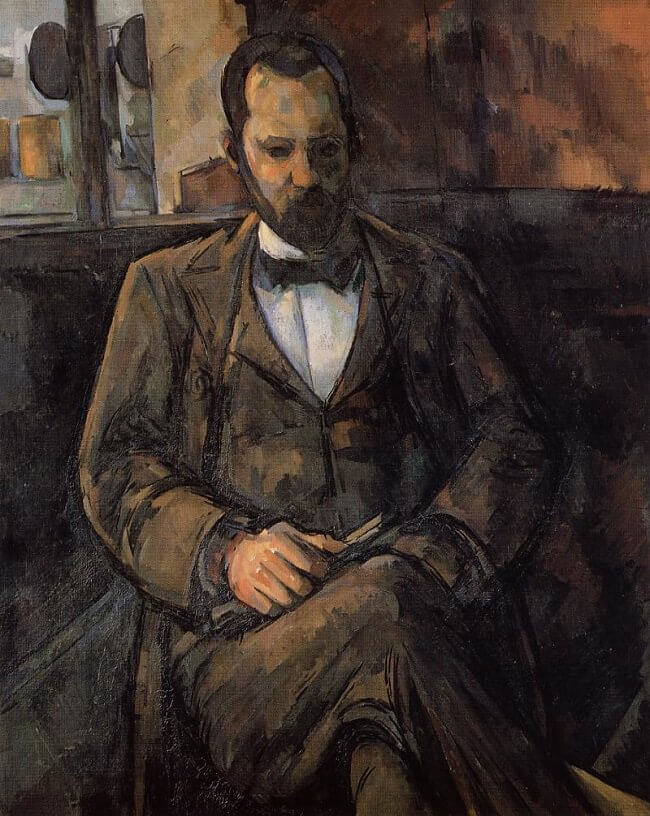

Portrait of Ambroise Vollard, 1899 by Paul Cezanne

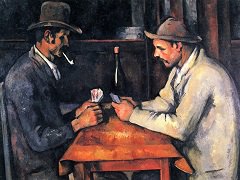

Ambroise Vollard had every right to grow tense. He had posed for the equivalent of two work weeks, not an easy investment of a dealer's time in 1899, when the avant-garde meant something: for artists at least, it could well mean poverty. In all this time, for days lasting into evening, Paul Cézanne commanded him to sit absolutely still, like Cézanne's Card Players, and the artist never did declare the portrait done. He merely abandoned it, Vollard, and modern art to their fate. In the painting, however, one could easily overlook the tense, restless surface, for everything seems to point inward.

These days one takes a seated portrait for granted. Photographers will do anything to give a subject dignity and to put a subject at ease. Once, however, those with sufficient wealth stood for their life-size portraits, and a still longer tradition demanded the clarity and reserve of head and shoulders alone. As art took on the middle class, women sometimes sat knitting or at the virginals, or businessmen sat to work at their accounts. In a seated, frontal portrait, however, as from Raphael or Diego Velazquez, a chair meant a throne, with a pope's hands gripping each of its arms as a sign of command. Rembrandt's late self-portrait plays on that convention, but it takes the birth of Modernism to bring inner visions fully to the surface.

Vollard, his lips pursed and his eyes almost lost in shadow, bows his head and crosses his legs. The hand close to his chest clenches a book or perhaps his papers, and the other lies buried between his knees. The only other object in the room, a trapezoid near his head, might stand for a second book, its covers shut tight.

It may take a few moments to notice the patches of bright color everywhere. One can miss them entirely in reproduction, but in person they keep vision from ever sitting still. Despite the fall of natural light from behind, Vollard's knuckles have the strongest highlights - as much an expression of physical and mental tension as of the presumed light source to his right. Other bright areas add to the volume and concentration of his high forehead. They give the painting an unstable center, too, in the near vertical of his shirt front. Cézanne declared that part of the painting a success.

Eleven years later, Picasso, too, painted Vollard as a study in restless intellectual inquiry, as also in a Picasso drawing. He surely had in mind an emblem of his own painting as well. Vollard's eyes narrow even further into slits, the bright shirt front fans outward, and that forehead seems in the process of exploding. At the height of Analytic Cubism, for once Picasso suppresses text, puns on the texture of materials, or hints of anything else in the room - almost to the point of inventing abstraction.

Throughout the 1890s and early 1900s, Vollard exhibited and sold works by Paul Cézanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso,Renoir and others, defining his position as a dealer in avant-garde art and shaping the reputations of those artists. Back then, a young dealer made a career by investing in art in cash, up front - and if Vollard turned handsome profits, so be it.