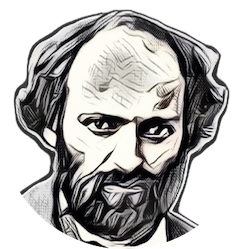

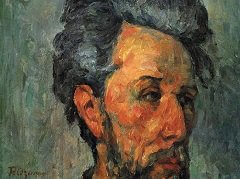

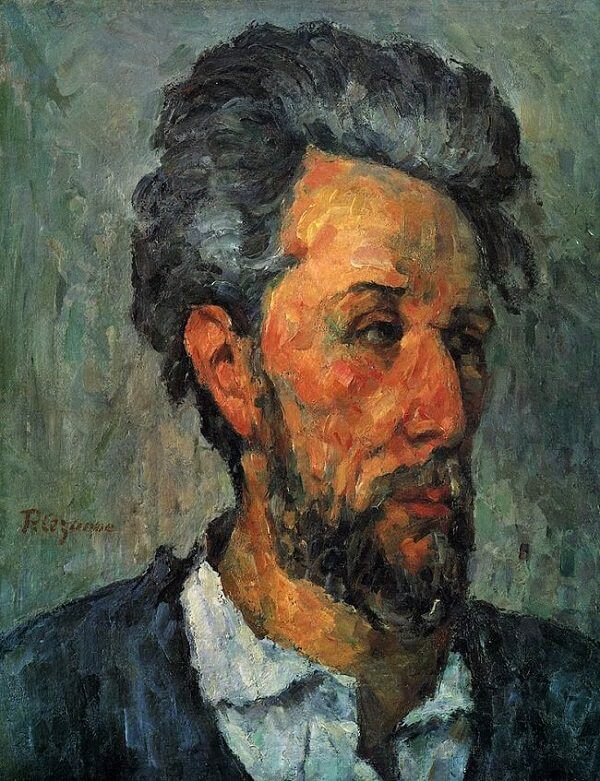

Portrait of Chocquet, 1876 by Paul Cezanne

Victor chocquet was a friend of Impressionists who has become a historical figure through his pure devotion to contemporary art. A minor government employee, without great means, he was caught by the beauty of Renoir's and Cezanne's works and collected these while they were still ridiculed by the critics and public. Both artists painted his portrait several times.

In Renoir's portraits, Chocquet appears a soft receptive nature, perfectly relaxed; he gazes gently at the observer. In Cezanne's painting, the features are no less sensitive, but there is in the bearing of the head, turned sharply to the side and culminating in the high mane of hair, an accent of grandeur, a reminiscence of the near-romantic portraits of the Napoleonic age. Such idealization is foreign to Impressionist portraiture; but we have seen before in the portrait of Boyer how Cezanne endows a friend with a romantic aura. Chocquet is conceived as a lean Quixotic type. The lengthening of the head is like the attenuation of El Greco's figures; here the cult of art replaces a religious dedication, with a similar selflessness and purity of spirit. It is a homage to a noble devotee, a man of independent conviction. In the portrait of his admirer, Cezanne speaks also of himself.

The head is seen in a curious perspective, as if through a glass that narrows the face and sharply foreshortens the sides. The features are extremely contracted, and the turn of the eyes, by reducing the force of their axis, also brings out the vertical of the face, which is prolonged further by the angularities of the upper brow and the similar opening of the collar.

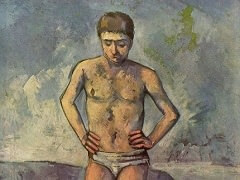

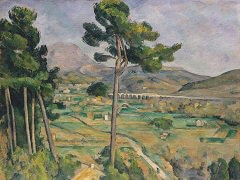

Compared to the Boy in a Red Vest, it is an advance in luminosity and freshness of color, like Cezanne's new landscapes. Outdoor tones replace the blacks and neutralized shades of the earlier portrait. And as in the landscapes, we follow the action of the brush everywhere, spirited and frank and creating a thick fleshy paste of pigment, rich in flicker, direction, and tone. The stroke is intense and direct throughout - in the background as in the head, in the hair as in the delicate features - but with a distinct movement in each part. It is nicely proportioned to the whole: small enough to permit subtle modeling, large enough to be perfectly visible as a constructive element of the whole. A few tiny red touches, capering and chaotic, liven the nose and cheek; and darker strokes, together with the edges of hair and beard, make an interesting, unstressed rhythm of curved lines. It is all built up without obvious trace of plan or guiding structural lines, as if from the spontaneous play of the brush in direct response to the man. Most remarkable of all - what we return to again and again - is the largeness of effect, the powerful possession of the space.