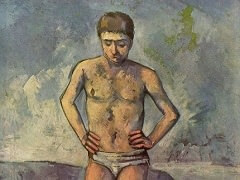

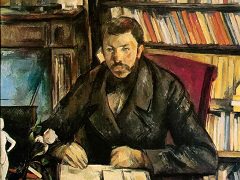

Portrait of Louis Guillaume - by Paul Cezanne

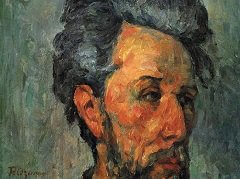

Before Cecanne's portraits, it has been asked whether the faces are expressionless masks or express an aloof, impassive state of mind. This uncertainty will hardly be felt before the portraits of Boyer or Chocquet, or some of Cezanne's self-portraits. But it is a real question for many of the later portraits and is indeed hard to answer because a portrait, besides being an image of an individual, is also a painting with its special problems of composition and color. If the artist projects his own nature into a portrait, that nature may be one indifferent to personality, it may itself be a personality that seeks to free itself from the difficulty of communication with others by creating a solitary expressive domain where it is master. It has been said that Cezanne painted the heads of his friends and family as if they were apples; but an artist so closed to the physiognomic would ordinarily content himself with still life or landscape or views of buildings. There is in Cezanne an evident desire for the human being; his retreats, his shyness, his often hysterical anxiety at encounters, never abolished this desire. He returns to man with hopes of understanding or love, but painting as a discipline governed by his need for a private world of mastership is already so strongly set in his nature as to impress its most characteristic methods upon his portraits. Yet he often surmounts this influence of the still life and the landscape and creates portraits of great insight and fellow feeling.

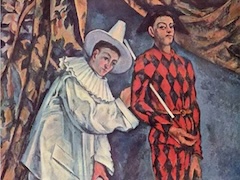

In the Portrait of Louis Guillaume, the son of friends of his wife's family, the subject is no challenge to the artist as a person. Yet there is a far-reaching abstraction of the head and body as elementary solid forms, the most advanced in the art of this time. No less uncommunicative than the face is the immobile body, in which we cannot imagine a gesture or movement. The muteness of the face represents perhaps the boy's unformed nature rather than Cezanne's detachment or feeling of an abyss between human beings; but it has also a nuance of shyness or reserve in keeping with the painter's sobriety and grave mood, which we feel in the cool, low-keyed color, the depth of the shadow tones, and the accented closure of forms within an atmosphere of revery. The whole has something of the somberness of his early works refined by the new discovery of color and his more contemplative approach. The tones of the face are pearly, lustrous, transparent, exquisitely delicate and pure; but the face itself as a human surface is without spiritual light; the eyes are lusterless and unfocused - they belong to a world of shadow. The dark cap of the hair has been cut into a severe pattern, and the features strangely disarrayed by a twisting of the axis of nose, mouth, and chin, a torsion continued in the knotted cravat which isolates the head from the body. This cravat is an extraordinary invention of form, related to the inner lines of the face, and echoed in the ornament of the wall. Through deviations from the inherent symmetries of the human being, and through the beautiful play of dark folds on the costume, the more regular, imposed geometrical form acquires an aspect of living strain and disorder.