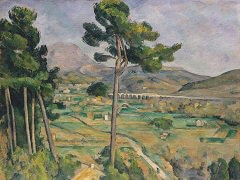

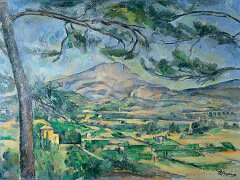

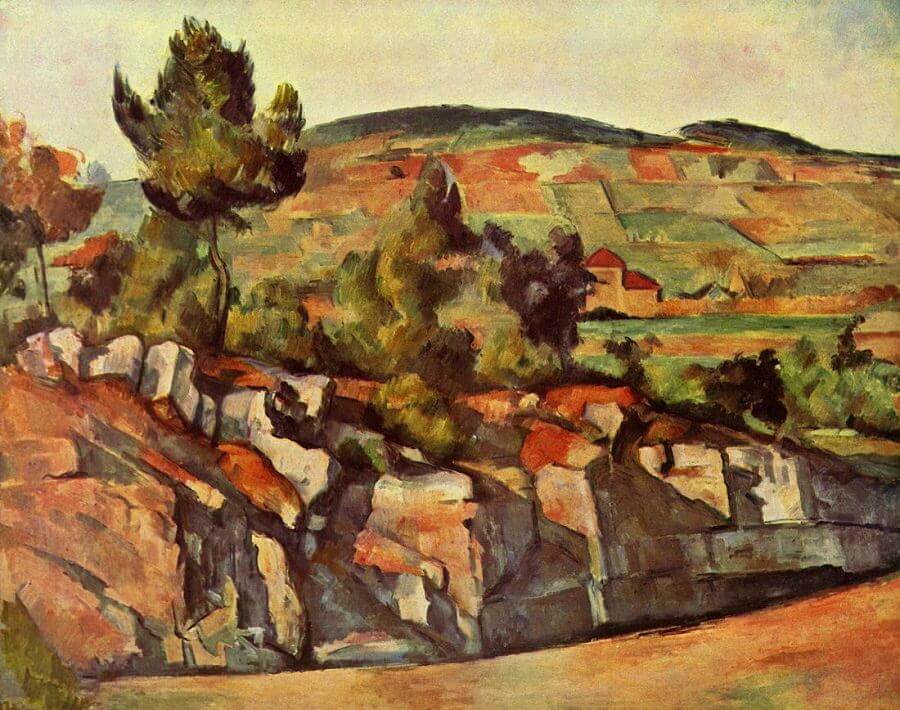

Mountains in Provence, 1886 by Paul Cezanne

In Mountains in Provence, 1886, the bare foreground sets off the landscape like a craggy shore viewed from a passing boat at sea. The theme is typical of one side of Cezanne's art, his vision of nature as a detached presence, solid and stable, something we see and cannot cross.

In this suspended vision, so beautifully composed, is a great span of feeling. We pass from the steep, fractured rocks - modeled, unbalanced, dramatically illumined, ruddy in the light and grey in the shadows - to the gently sloping, rounded hillside with delicate surface markings under a soft light; from the bent, jagged tree which breaks the horizon to the smaller echoing trees, settled against the quiet hill; and beyond to the pale void of the sky.

The power and harmony of the scene, so passionate and still, rest on a most subtle invention of large contrasts, small gradations, and interwoven accords. We feel the ultimate balance of opposed, unstable forces, but we cannot isolate them as distinct parts; each is so complex within itself and involved in so many relations with neighboring forms and tones. What looks at first like an explicit geometric design in the strange symmetry of tilted horizontal bands soon reveals itself as more natural and free. The austere painting of this solitary world sacrifices little of the naturalness of the encountered scene. The rocks, like a town in their cleft upright planes with red tops like roofs - these recall the buildings in the distance - have also chaotic, accidental structures and vaguely organic shapes which merge with the trees.